As I manage to eke out a little more time now for personal projects, since

TenFourFox is coming to a close and

the OpenPOWER JIT is developing at record pace, it's time to dust off some older items I've really neglected. This last week I started by updating the Incredible KIMplement, my

MOS/Commodore KIM-1 emulator for the Commodore 64.

No, that's not a joke. The KIMplement runs real KIM-1 code using a software 6502 core I've christened "6o6" (6502-on-6502). 6o6 implements protected memory, exception handling and all legal NMOS instructions. In addition, the KIMplement not only emulates those famous six seven-segment LEDs and the hex keypad, but also is one of the few KIM-1 emulators that emulates a TTY connection (an old-school ASR-33) and a KIM-4 expander with 16K of RAM, allowing you to run "big programs" too.

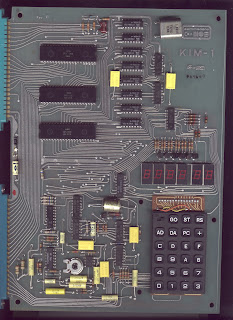

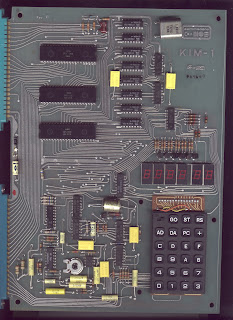

The KIM-1 is one of the earliest single-board computers, at least in the sense we conceive of them today. It was introduced in 1976 as an enticement for engineers to play with the MOS Technology 6502 which was then the cheapest microprocessor on the market. MOS had just gotten its pants sued off by Motorola, who did not like the prospect of an inexpensive drop-in replacement for their 6800 CPU; the MOS 6501 was completely pin- and bus-compatible, and where the 6800 cost $179 the 6501 was priced at just $25. The "lawsuit compatible" 6502 was just as cheap, but because the pins had been rearranged, couldn't be substituted without additional design work. The KIM-1 provided a platform for engineers to become more accustomed with the 6502, featuring a 1MHz CPU, 1K of RAM, cardedge I/O, a keypad, LEDs and in-ROM support for teletypes, punch tape and cassette tape, for only $245.

MOS expected this would be a low-volume item mostly of interest to circuit designers. Instead, hobbyists bought them in large numbers because it was easily the least expensive microcomputer you could purchase at the time. With a KIM-1 at its center, you could have a full system with teletype, power supply and cassette storage for around $500. No other system came close to competing on cost. When Commodore Business Machines bought the ailing MOS in 1977, they wisely kept producing the KIM-1 until 1979 even after the introduction of the PET. Several clone systems exist, most notably including the Synertek VIM-1/SYM-1, as well as one unusual clone I'll talk about in a moment. I am the proud owner of four KIMs (including an original pre-Commodore KIM-1) and they all work.

I don't know if KIMplement's CPU core could be truly considered "virtualizing" the 6502, but it's more than just a naïve emulation. Rather than manually setting results and flags, the core looks at the guest instruction and runs the same instruction (or a safe variant) in the core context so that all the side effects, in particular changes to the status register, occur "for free." There is no way that a Commodore 64 at 1.0225MHz (or, worse, 0.978MHz for PAL) can do full-speed emulation of a KIM-1 running at 1MHz, but because there is much less code running per instruction, I think this scheme is probably near the fastest way a 6502 can run "untrusted" 6502 code. In practice it is about 35-50 times slower than native code, and this upsets programs that use tight timing or cycle counts, but it's still absolutely enough to actually "do things."

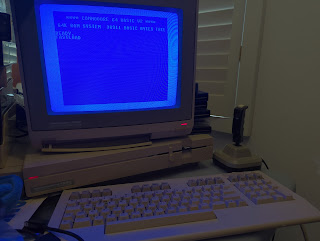

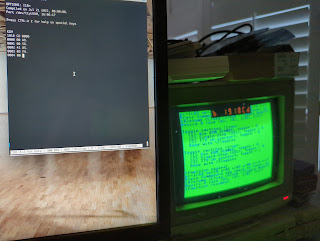

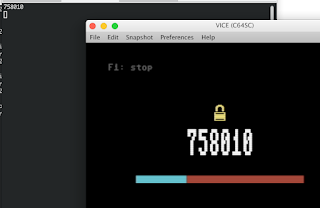

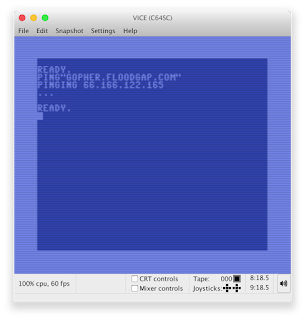

What sorts of things? Besides a couple LED-based games (originally Jim Butterfield's version of Lunar Lander, and I also added the misère game variant Black Match) and toy applications, you can run Tom Pittman's Tiny BASIC in the TTY, and with the bug fixes in 0.2b now you can successfully run FOCAL-65:

This screenshot in VICE shows the emulated 64 running a full FOCAL-65 program to manually compute square roots using Newton's method. It takes it a few seconds to do each iteration, but it all works. This is also a good demonstration of the FOCAL programming language itself including its unusual "floating point" line numbers (actually module and line), which it inherited from its more complex ancestor JOSS.

For this version of the emulator (0.2b), I finally finished some performance improvements to the CPU core that had been gestating in my mind for literally years -- the last version of the KIMplement was released in 2006! -- and also fixed a problem with the TTY emulation where typing characters could get out of sync under CPU load. It can still drop keystrokes if you overflow the Kernal keyboard buffer, but it's a lot smoother generally. I also worked around a bug in VICE where, if you try to load files from a directory on the host machine, the RENAME-the-file-to-itself test used to check for the file's presence doesn't work (a real 1541 would respond with error 63 FILE EXISTS but VICE says 0 OK).

The other bug I fixed was caused by the CPU core, but can't be fixed in it. The 6502 has a decimal flag which can be set in the status register and causes add and subtract instructions to operate in binary coded decimal (e.g., $90 - $01 normally is $8F, but in BCD mode it's $89). Famously, or perhaps infamously, the Commodore 64 Kernal IRQ doesn't turn off the decimal flag, and there is at least one SBC in the normal execution path. Because 6o6 executes instructions for their side effects, if a program had previously set the decimal flag (and this is not at all uncommon in KIM-1 code) it needs to be on for those math operations. The usual solution is to turn on the interrupt flag first with SEI to suppress IRQs while decimal mode is on, but the normal state of guest code is to have the interrupt flag clear because the KIM-1 doesn't have this problem. If an IRQ hits right that moment, the IRQ will be executed with the decimal flag on, and possible unexpected behaviour could result.

This is an extremely infrequent occurrence, but in a long-running system "infrequent" is a synonym for "inevitable." This can't be efficiently solved in the core because there is no atomic method for controlling two flags at once. A better solution is very simple: we just make a patched IRQ that clears the decimal flag explicitly, and calls the normal Kernal IRQ. I did the same for NMIs as a belt-and-suspenders approach.

The eventual goal is to open-source the KIMplement, and in particular 6o6, but I want to have another demonstration application for 6o6 as well before I do. A small multitasking general-purpose kernel sounds like an ideal way to show off how it works.

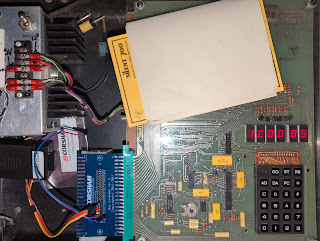

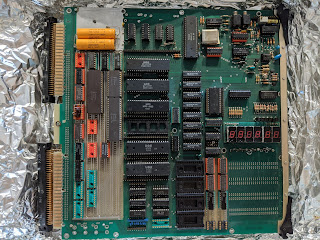

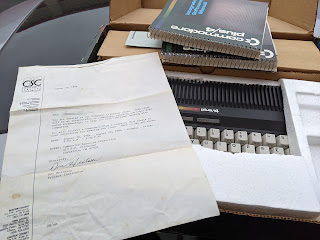

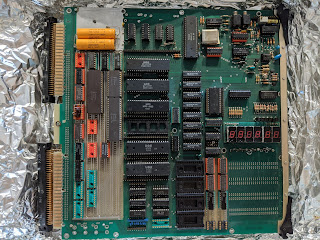

On my main KIM-1 site I also put in a few words about the microproducts Superkim. This 1979 variant of the KIM-1 was developed in Redondo Beach by Paul Lamar, who had been using KIM-1s for automotive performance testing but was unsatisfied with their expansion capacity. Unlike the hobbyist audience of the KIM-1, the Superkim is all business. The unit in my possession was clearly in a card cage; the hex keypad was never even fitted. It uses a custom board rather than a modified KIM-1 with sockets for RAM, ROM and up to four 6522 VIAs (this unit has 4K of static RAM and a Rockwell R6502P), and sports a full prototyping breadboard on-unit. But its most noticeable (and, I might add, intimidating) characteristic is the 200 gold wirewrap pins penetrating the board:

I have no idea what the sam heck this board was doing, but it clearly did something major in whatever its application was. Don't ask me to power this thing up because I'm worried I'll short something out somewhere. I don't know how many of these were ever sold and Commodore and MOS seem to have had nothing to do with its development.

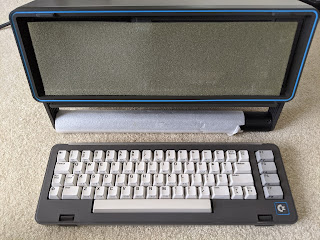

Of the clones I find the Superkim the most interesting. While many people mention the Rockwell AIM-65 as a clone (my unit is above), and it is strongly based internally on the KIM-1, its substantial expansion (wide alphanumeric LED screen, full keyboard, printer) would not make it generally recognizeable as such. I think the Synertek VIM-1/SYM-1 are more characteristic, though that is one unit I don't personally possess.

In the future, and hopefully that future isn't in another 15 years, I want to add actual cassette support (right now you just dump memory to and from disk) and maybe support for one of the hi-res video boards like the Visable. It may also be worth trying to port the KIMplement to a faster 6502-based system like the Commodore Plus/4 or the Commodore 128 in 80-column mode, or maybe even the Apple IIgs, though all of these would need a solution for the sprites I currently use for the LEDs. (Okay, you Atari freaks, I know, I know.) The KIM-1 is a great little machine and surprisingly capable. The fact all of mine have survived over four decades proves they don't make them like they used to.

You can download a .d64 or .sdas of the Incredible KIMplement and its demo applications, or read more about the KIM-1.